The Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation has announced that Moreau Kusunoki Architectes is the winner of the Guggenheim Helsinki Design Competition. The French architecture firm’s design, Art in the City, is proposed for a site at Eteläsatama on Helsinki’s South Harbor. The Finnish outpost would be the Guggenheim’s fifth museum, and its third in Europe, if it is constructed.

See our previous coverage: Guggenheim Helsinki? Not so fast…

The Guggenheim Foundation has museums in New York, Venice, and Bilbao, and another under construction in Abu Dhabi. Plans for a museum in Helsinki began in 2011 with a proposal that called for the city and state to provide €130 million for construction, €23.4 million for a licensing fee plus another €2 million annually, half the estimated annual operating costs of €14.4 million, and a merger with (or a closure of) the Helsinki Art Museum.

The city rejected the plan, and the Guggenheim submitted a revised proposal that removed the licensing fee, halved the operations fee, reduced projected operating costs, and spared the Helsinki Art Museum. Additionally, an independent study estimated that the new Guggenheim could generate $56 million for the city each year and create 500 permanent jobs in and around the museum. The new proposal moved forward and the Guggenheim announced an international design competition last June.

By September, the Guggenheim Helsinki Design Competition received 1,715 entries from 77 countries. In December, the jury shortlisted six proposals for further concept development. The six designs – by AGPS Architecture (Zurich), Asif Khan (London), Fake Industries Architectural Agonism (Brooklyn), Haas Cook zemmrich STUDIO 2050 (Stuttgart),SMAR Architects (Madrid), and Moreau Kusunoki Architectes (Paris) – were presented in a public exhibition at the Kunsthalle Helsinki this spring.

The winning team of Moreau Kusunoki Architectes is a Parisian firm founded by husband and wife Nicolas Moreau and Hiroko Kusunoki. They have designed other cultural projects including a theater in Beauvais, a contemporary art center in Marseille, and a university building in Bourget du Lac. Their proposal for Helsinki combines traditional building materials in a transparent campus that opens to the sea and the city.

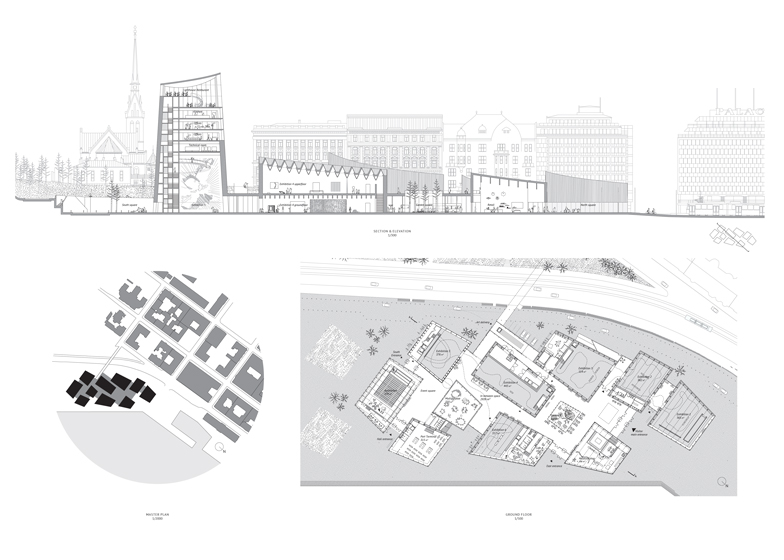

Art in the City is comprised of nine pavilions connected by glass-walled corridors, with views onto Helsinki’s South Harbor and Observatory Park. Six of the pavilions will contain galleries totaling about 4,000 square-meters of exhibition space, comparable in size to the Guggenheim’s iconic building in New York. The three remaining pavilions will contain a performance hall, educational space, administrative offices, and collections facilities. Glassed-walled gardens and concave roofs with clerestories will permit light into the buildings. The tallest pavilion will contain a restaurant under a glazed top, and has been called a lookout tower or lighthouse.

The exteriors will be clad in charred black wood, which is traditional in Finland and often seen on rural churches. The site will be oriented toward South Harbor with a long promenade and will be connected to Observatory Park by a pedestrian bridge. An official statement from the eleven-member jury describes that they “found the design deeply respectful of the site and setting, creating a fragmented, nonhierarchical, horizontal campus of linked pavilions where art and society could meet and intermingle.”

The project is not without opposition. Beyond the city’s rejection of the 2011 proposal, some Finns are dubious of the Guggenheim’s costs and benefits. While the “Bilbao effect” has been touted in support of cultural projects in cities around the globe, the Guggenheim doesn’t always produce winners. It previously had museums in Las Vegas and Berlin that closed in 2008 and 2013, respectively, and is now accused of complicity in labor abuses and human rights violations in the construction of the Abu Dhabi project.

Moreover, Finns are not entirely convinced that Helsinki needs the Guggenheim. Like other Scandinavian countries, Finland has a distinct visual culture of modern design and local artists. In contrast, the Guggenheim is an international brand of mega-museum. The only other major cultural site in Helsinki by an international architect is the Kiasma, a contemporary art museum designed by Steven Holl (New York). Kiasma opened in 1998 to some opposition and concerns about the incursion of starchitecture, but since then it has become a much-admired feature of the city.

Helsinki has given provisional approval for the project site at Eteläsatama, and the Moreau Kusunoki design seems incredibly refined, but don’t expect a groundbreaking event just yet. Even if Helsinki’s city board accepts the Guggenheim’s proposal, it will still need approval from the eighty-five-member city council. Finland is ascendant but still facing austerity, so public funding for a private museum may be a bigger competition than the one for the design.