In October 2019, the Louvre opened an unprecedented exhibition of works by Leonardo da Vinci. The show marked 500 years since the death of the Renaissance master and it was the largest-ever collection of his works brought together in one place. After more than ten years of research and planning, the once-in-a-lifetime exhibition offered an exhaustive catalogue of da Vinci’s oeuvre and set a record for attendance. One excluded painting, though, is a problematic footnote.

The Louvre is the world’s most visited museum, with about 10 million visitors each year, and the largest, displaying about 35,000 pieces from its collection of more than 480,000 works of art. Among them all, Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa is the most famous, seen by about 8 million each year. While La Joconde, as she is called in French, is the superlative, the Louvre owns four other paintings by da Vinci – a third of the 15 or so major works attributed to him – and 22 of his drawings.

For the 2019 exhibition, the Louvre borrowed paintings, drawings, and manuscripts from the Hermitage, the Met, the Royal Collection, the Vatican Museums, and others that rarely lend such works. The catalogue included 179 entries, with at least nine paintings and 80 drawings by da Vinci, as well as works by followers including Andrea del Verrocchio, Giovanni Antonio Boltraffio, and Marco d’Oggiono.

The Mona Lisa was not included in the exhibition – the painting is permanently installed in the Louvre’s largest room, the Salle des États, which has some 30,000 visitors each day. The temporary exhibition, in the Hall Napoléon, was expected to accommodate only about 7,000 visitors each day, but was seen by more than a million people over its 104-day run, setting an attendance record and culminating in a non-stop opening for 81 hours during the final weekend.

When we visited in February 2020, The Vitruvian Man was not on view. The archetypal drawing that represents mathematical proportions of the human body is owned by the Gallerie dell’Accademia in Venice, where it is typically shown only once every six years due to its fragility and sensitivity to light. The Louvre’s request to borrow the work was first approved, then challenged in court by the conservation group Italia Nostra, but ultimately sent to Paris as part of an exchange agreement signed by the culture ministers of Italy and France which allowed the drawing to be shown during the exhibition’s first eight weeks from October to December 2019.

Also missing from the exhibition was a version of The Virgin of the Rocks, the name of two paintings of the same subject, one belonging to the Louvre and the other to the National Gallery in London. The Louvre’s painting is the earlier of the two, unrestored, and attributed entirely to da Vinci. The National Gallery’s version was considered to have been painted by assistants, until 2010 when restoration work revealed details that led curators to conclude it had been painted by da Vinci. The attribution is not universally accepted, and in any case, the painting remained in London to be the centerpiece of a simultaneous exhibition there.

The work most conspicuously absent from the exhibition, the Salvator Mundi, is more disputed than the attribution of The Virgin of the Rocks; more complicated than the loan of The Vitruvian Man; and maybe, briefly, almost as famous as the Mona Lisa.

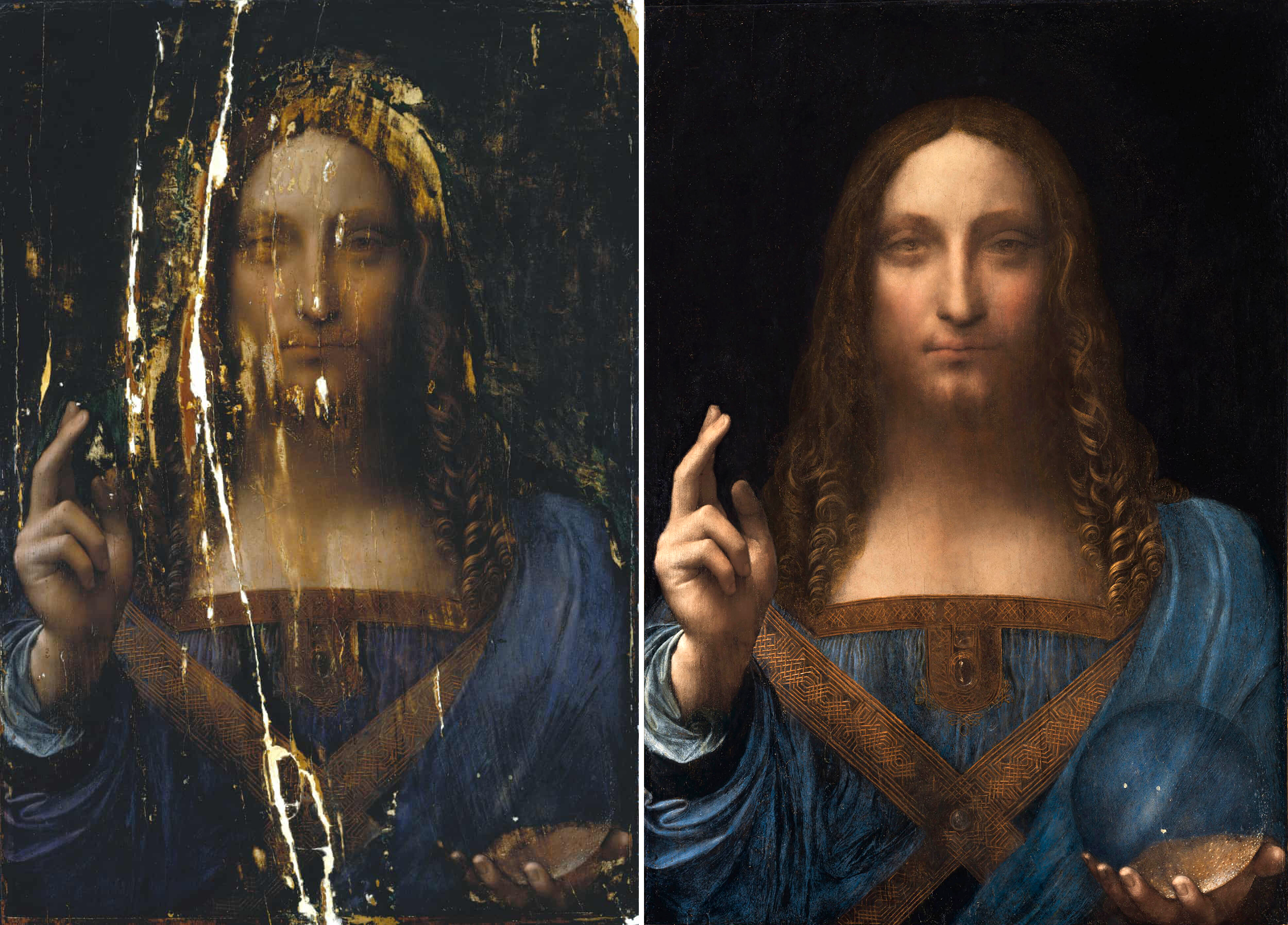

Whereas other major works by Leonardo da Vinci are well established with provenance – chronology of ownership and documentation that help determine the authenticity of a work of art – the Salvator Mundi has no certain history. Art dealers Alexander Parrish and Robert Simon purchased the painting, labeled “after Leonardo,” from an auction in New Orleans in 2005. It had been in private collections since around 1900, but its location before that is unknown. They paid $1,500, on speculation that it could be a long-lost master work, and commissioned a restoration of the badly damaged painting.

The work’s conservator, Dianne Modestini, a faculty member at the Conservation Center of the Institute of Fine Arts at NYU, was the first to claim that the Salvator Mundi painting was a da Vinci. In removing previous overpainting she discovered pentimenti and sfumato effects that she compared to the Mona Lisa, and subsequently carried out a restoration process that painted over nearly the entire panel.

The original work is thought to have been painted around 1500, but most of what we see today was painted by Modestini after 2006. According to Frank Zöllner, an expert on da Vinci and faculty member at Universität Leipzig, “You have the old parts of the painting which are original – these are by pupils – and the new parts of the painting, which look like Leonardo, but they are by the restorer. In some part it’s a masterpiece by Dianne Modestini.”

In 2011, notwithstanding its provenance and heavy restoration, and without consensus, the Salvator Mundi was included in an exhibition at the National Gallery in London as an “autograph” work, achieving attribution. In 2013 the Swiss art dealer and freeport developer Yves Bouvier purchased the painting from Parrish, Simon, and a third partner for $83 million, then sold it to the Russian billionaire oligarch Dmitry Rybolovlev for $127.5 million. In 2017, after a marketing tour de force, Christie’s sold the painting at auction for a record $450 million.

News about the most expensive painting ever sold became speculation about the buyer – it was Mohammed bin Salman, the Crown Prince of Saudi Arabia – which became speculation about where it would be seen again. It was expected for some time that the work would be a gift for the Louvre Abu Dhabi, which had just opened, as a diplomatic gesture between Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The painting didn’t appear there, however, and Abu Dhabi’s Department of Culture and Tourism refused to discuss it.

Speculation about the painting’s whereabouts and potential future exhibition shifted in early 2018 when French President Emmanuel Macron hosted bin Salman for a private tour at the Louvre. The visit coincided with negotiations for France to develop museums, cultural sites, and infrastructure for Al-‘Ula, Saudi Arabia’s $20 billion project to make a cultural tourism destination, a deal which could surpass the $1 billion agreement for the Louvre Abu Dhabi and could position Saudi Arabia’s Al-‘Ula to eclipse Abu Dhabi’s investments in museums and culture at Saadiyat Island. With this, it became possible that a showing of the Salvador Mundi at the Louvre could signify France–Saudi Arabia relations surpassing the UAE, all with the soft power of art.

When the Louvre opened Léonard de Vinci in October 2019, the Salvator Mundi was not included in the exhibition, but a similar work indicates what could have been expected. Another Salvator Mundi – there are at least thirty copies or variations of the subject painted by da Vinci’s assistants and followers – known as the Ganay version was labeled as “Atelier de Léonard de Vinci,” painted by the workshop of da Vinci. Though the National Gallery had attributed the Salvator Mundi to da Vinci in 2011, the Louvre could have accepted or rejected the attribution, either of which may have been problematic for a work with questionable authenticity now owned by a Saudi prince.

In March 2020, after the exhibition had closed, it was reported that the Louvre had printed, but not released, a 45-page publication on the Salvator Mundi. The implication is that the painting was expected to be included in the exhibition, but removed at some late point. Because the Louvre’s policy not to comment on a work that it has not shown precluded any statements about the Salvator Mundi or the book’s release, the world’s most authoritative museum, which holds a majority of known paintings by da Vinci, has not weighed in on the controversial work. The mysterious painting is missing from view but may not actually even be a lost da Vinci.