Last month, the Solomon R. Guggenheim Foundation and Helsinki city officials announced an international design competition for a proposed new museum in the Finnish capital. The Guggenheim proposal has been met with disapproval in Helsinki since 2011, and there is no certainty that the design competition will gain public support for the project.

The Guggenheim Foundation is a leading institution for the collection, preservation, and research of modern and contemporary art. It has word-class collections, a considerable endowment, and operates several international museums. The Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York opened in 1959, and its renowned modern spiral building is the only museum ever designed by Frank Lloyd Wright. The Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice occupies the Palazzo Venier dei Leoni, an 18th-century palazzo along the Grand Canal. The Guggenheim Bilbao and the forthcoming Guggenheim Abu Dhabi were each designed by starchitect Frank Gehry.

Among these, the Guggenheim in Bilbao provides the model for the proposal in Helsinki. In 1991, the Basque government launched the project with a budget of $100 million for construction, $50 million for art acquisitions, $20 million for a one-time fee to the Guggenheim, and ongoing subsidies for operating costs. From its opening in 1997, the Guggenheim Bilbao has been an economic success. There were nearly 4 million tourists in the first three years, generating €500 million in regional economic activity and development that transformed the blighted port area into the Basque Country’s top tourist destination. The success has been so great that the “Bilbao effect” is a regular description for the urban renewal that other cities try to replicate by developing art museums and cultural attractions.

In Helsinki, the Guggenheim’s first proposal in 2011 called for the city and state to provide €130 million for construction costs, €23.4 million for a one-time licensing fee to the Guggenheim, €2 million annually for an operations fee to the Guggenheim, and half of the estimated annual operating costs of €14.4 million. The proposal also included a merger with (or a closure of) the Helsinki Art Museum. Most city residents opposed the project and Helsinki’s city council rejected the plan in 2012.

In 2013, the Guggenheim Foundation submitted a revised proposal for Helsinki. In short, it eliminates the merger with Helsinki Art Museum; removes the €23.4 million licensing fee, now to be funded by private sources; halves the €2 million operations fee to €1 million annually; reduces projected operating costs by 10 percent; increases visitor projections by 10 percent; and, notably, proposes a different building site at Eteläsatama on the opposite side of Helsinki’s South Harbor and away from the primary historical areas.

Critics of the plan identify that the Guggenheim would benefit without taking any financial risk, as Helsinki and Finland are expected to cover all of the costs. Moreover, the Finnish Ministry of Culture has no budget for the project so that funding would require either new taxes or budget cuts for other museums and cultural institutions. Most Finns are dubious of the proposal, which asks Helsinki to subsidize the Guggenheim. Even if some politicians and developers are eager to attract the Guggenheim brand with some new starchitecture to boost tourism, the desired Bilbao effect may be incongruous for Helsinki.

Bilbao was largely industrial until the decline of its port, mining, and ironworks industries in the 1980s. The Basque government’s investment in the Guggenheim’s construction and operations repaid the region nearly within a year of its opening, with €500 million in new economic activity within three years. With the Guggenheim as the centerpiece of the city’s revitalization, tourism in Bilbao increased from 25,000 in 1995 to more than 1 million in 1998, and stabilized at 615,000 since 2009.

Helsinki generates about one-third of all of Finland’s GDP and is on par, per capita, with Stockholm and Paris. The Finnish capital, however, does not expect such stunning figures as Bilbao. The Guggenheim Foundation projects €41 million in economic impact based on annual attendance of 550,000 visitors – more than twice the number of visitors to Helsinki’s popular contemporary art museum Kiasma, and even more than the renowned and relatively near Moderna Museet in Stockholm. The Bilbao effect will not happen in Helsinki if these projections fall short, and certainly not if the Guggenheim’s funding decreases support for the Helsinki Art Museum, Kiasma, and other arts institutions.

If Bilbao is not analogous to Helsinki, what about other global museum outposts? The Louvre in Lens, the Pompidou in Metz, the forthcoming Guggenheim and Louvre museums in Abu Dhabi… None of these projects are comparable to the proposal for a Guggenheim in Helsinki.

The Louvre-Lens, which opened in 2012, and the Pompidou-Metz, which opened in 2010, are extensions of national museums within France. They function to decentralize the national collections beyond Paris, in order to be more accessible to the entire country. Both museums have increased provincial tourism and redevelopment, but these are secondary results to the primary investment of building museums to extend the national collections.

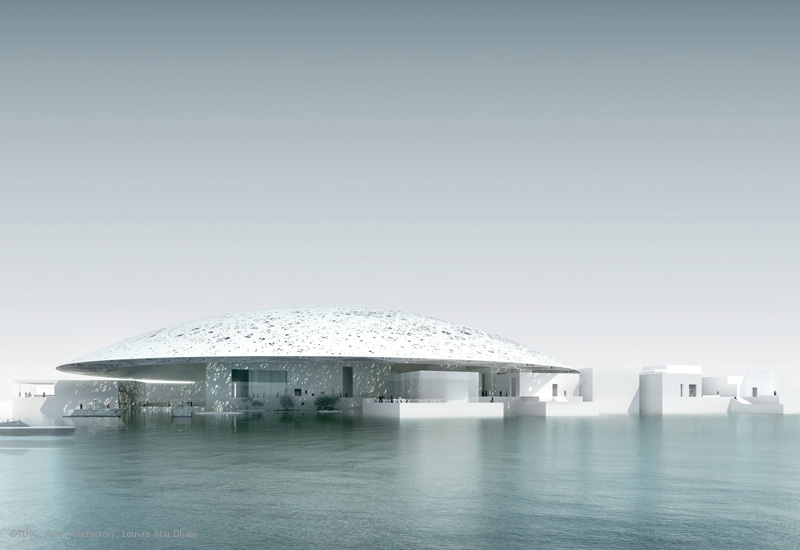

Abu Dhabi is incredibly new, wealthy, and populated with expatriates building a horizon of starchitect skyscrapers. The UAE has an incredibly rich cultural history, but relatively little material culture or visual arts. The Louvre Abu Dhabi, designed by Jean Nouvel and scheduled to open in 2015, and the Guggenheim Abu Dhabi, designed by Frank Gehry and scheduled to open in 2017, are funded by a city that is incredibly wealthy in capital but not in visual arts. Abu Dhabi’s deal with the Louvre, including construction costs and ongoing support, will total more than $1.3 billion over 30 years. Abu Dhabi’s deal with the Guggenheim Foundation is not reported but is assumed to be comparable. In both cases, one of the world’s wealthiest cities is commissioning new museums for cultural rather than economic development.

There is no precedent for the Guggenheim’s model of expansion and branding. Bilbao is the model for urban renewal by cultural investment, but can it work in Helsinki where the projected figures are both optimistic and modest? A design competition for the museum building was announced in June 2014 and the jury is expected to select a winning architect in a year. Then, Helsinki will decide again whether the Guggenheim’s brand will become part of the Finnish art world.