During the Hellenistic period – from the death of Alexander the Great in 323 BC to the establishment of the Roman Empire in 31 BC – Greek power and cultural influence were at their peak throughout the Mediterranean and Macedonia. The vast empire was controlled by dozens of generals and rulers, and a new market for portraits was formed with the development of bronze as a primary artistic medium.

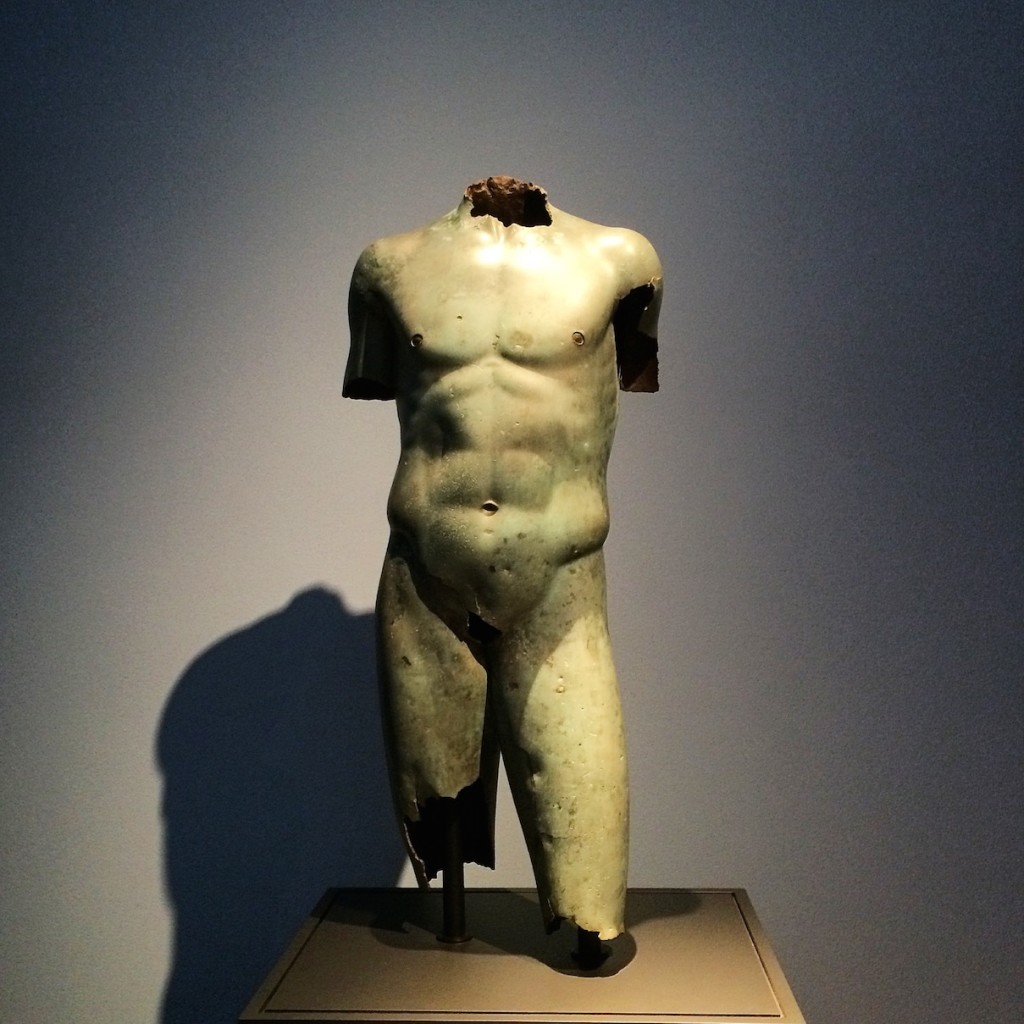

Classical Greek sculpture transitioned from idealized marble gods toward detailed and realistic bronze portraits in the Hellenistic period, and Greek sculptors were prolific across the empire with the production of statues in multiples. There are thousands of empty pedestals at ancient sites, but relatively few bronzes survived from antiquity. Most were melted down for reuse, often by the Romans, and others were buried or lost at sea.

Ironically, many of the Hellenistic bronzes known today were preserved by being buried by volcanic eruptions and submerged by shipwrecks. They have been recovered at sites such as Herculaneum, and from the Adriatic and Aegean Seas. Some 200 Hellenistic bronzes are known to exist in the world, and about 50 of them are now on view together at the Getty.

It seems like a superlative to call Power and Pathos is a once-in-a-lifetime exhibition, but it’s true. One-quarter of all the world’s Hellenistic bronzes are currently in one place. Curators spent seven years organizing loans, and you could fill your passport trying to see them all otherwise. These ancient works are on loan from museums in the US, England, Denmark, France, Spain, Italy, Austria, Greece, Croatia, Bulgaria, Tunisia, and Georgia. They are rare and hard to get, and this exhibition is a big deal.

The Getty typically shows antiquities at the Getty Villa in Malibu, which is designed after the Villa of the Papyri at Herculaneum and is dedicated to the study of ancient art from Greece, Rome, and Etruria. Instead, Power and Pathos is at the Getty Center, which is like a modern Acropolis above Los Angeles. Galleries there provide more space and natural light, and can accommodate more visitors than the Villa.

In the first gallery, The Spinario from Rome’s Musei Capitolini is paired with The Castellani Spinario from the British Museum. The bronze version likely predates the marble, and provides evidence of borrowed aesthetics with a 5th century BC head type, originally intended for another sculpture, combined with a later Hellenistic body.

Another gallery pairs two athletes with dramatic lighting and cast shadows. The Ephesian Apoxyomenos from Vienna’s Kunsthistorisches Museum and The Croatian Apoxyomenos from the Croatian Ministry of Culture are both assumed to be early Roman replicas of a Greek work from the 4th century BC. The figures are nearly identical in scale, but the Croatian work shows greater refinement and is better preserved with copper accents.

The most fascinating work in the exhibition might be the Portrait of a Boy from the collection of The Archaeological Museum of Herakleion. The figure wears a long cloak with sandals, and has an incredibly detailed and realistic face. More than any other, its expressive face is a specific portrait with detailed realism. The identity of the subject is unknown, of course, but the individualized face is as representational as any figure could be.

The Getty Bronze is contrasted with a similar but less intact version on loan from Athens. The Getty’s Herm of Dionysos is paired with another, remarkably by the same artist, from Tunisia. Pairs like these provide an incredible aesthetic experience, with enough works to overview the transitional period of Hellenistic bronze and demonstrate that they achieved levels of production and realism that were not matched again until the early Renaissance.

Power and Pathos: Bronze Sculpture of the Hellenistic World will close at the Getty on November 1, 2015. The exhibition was previously at the Palazzo Strozzi in Florence, Italy, and will travel to the National Gallery of Art in Washington, DC after it leaves the Getty. Not every object has traveled, however. The Getty Bronze, for example, was not loaned for the Italian exhibition, and the exhibition catalogue includes The Satyr of Mazara del Vallo, which has not been on exhibition.