After a record-breaking year in which global art auctions exceeded $16 billion, the world’s largest auction houses have resumed the risky practice of guaranteeing minimum prices for very expensive lots. Christie’s and Sotheby’s had mostly abandoned guarantees in late 2008, and observers are keen to speculate about their return. February sales with works by Monet, Cézanne, and Picasso are primed to set new records.

In guaranteed transactions, Christie’s and Sotheby’s promise sellers a minimum price for a work of art notwithstanding the actual final sale price. If the work exceeds the guaranteed minimum, the auction house and the seller split the extra amount. If the guaranteed minimum is not met, the auction house takes a loss to make up the difference to the seller.

Guarantees can benefit the auction houses with additional revenues, but they risk millions of dollars if sales fail to meet minimum prices. Until recently, most guarantees were underwritten by independent financiers who shared the profits, or alternatively purchased the art themselves to meet the guaranteed sale prices. Since late last year, Christie’s and Sotheby’s have hedged their own funds to guarantee the sale prices.

Critics complain that auction houses may promote guaranteed works more than those in which they have no stake, and that external guarantors gain an unfair advantage when they know the guaranteed minimum for works they are bidding on. What’s more considerable, however, is how much risk the auction houses are exposed to if the market falls unexpectedly.

Guarantees are one response to shrinking margins, which are primarily from premiums on sale prices and are increasingly eroded due to competition for the most expensive consignments. Christie’s and Sotheby’s make a multi-million dollar bet with each guarantee that the market will only continue to increase.

Among the upcoming lots with guaranteed minimums are several works by Claude Monet. Sotheby’s will have five Monets in its Impressionist and Modern Art sale in London on February 3 with a combined estimate of up to $106 million. The most significant, with guarantees from both Sotheby’s and an external guarantor, is Le Grand Canal, which is estimated for more than $30.6 million. The painting has been on loan to the National Gallery since 2006 and the consignor is not identified.

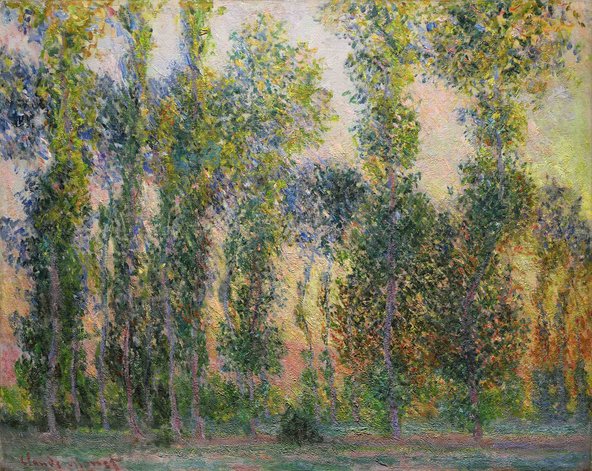

MoMA – with notoriety – has consigned Monet’s Les Peupliers à Giverny. It was painted in 1887, three years before the artist acquired his property at Giverny. Les Peupliers has an auction guarantee with an irrevocable bid, estimated above $13.6 million.

The other Monets in the February 3 sale include L’Embarcadère (1871), Vase de Pivoines (1882), and Antibes Vue de la Salis (1888), each from private collections. The works have been previewed in Taipei, Hong Kong, and New York in advance of the London sale.

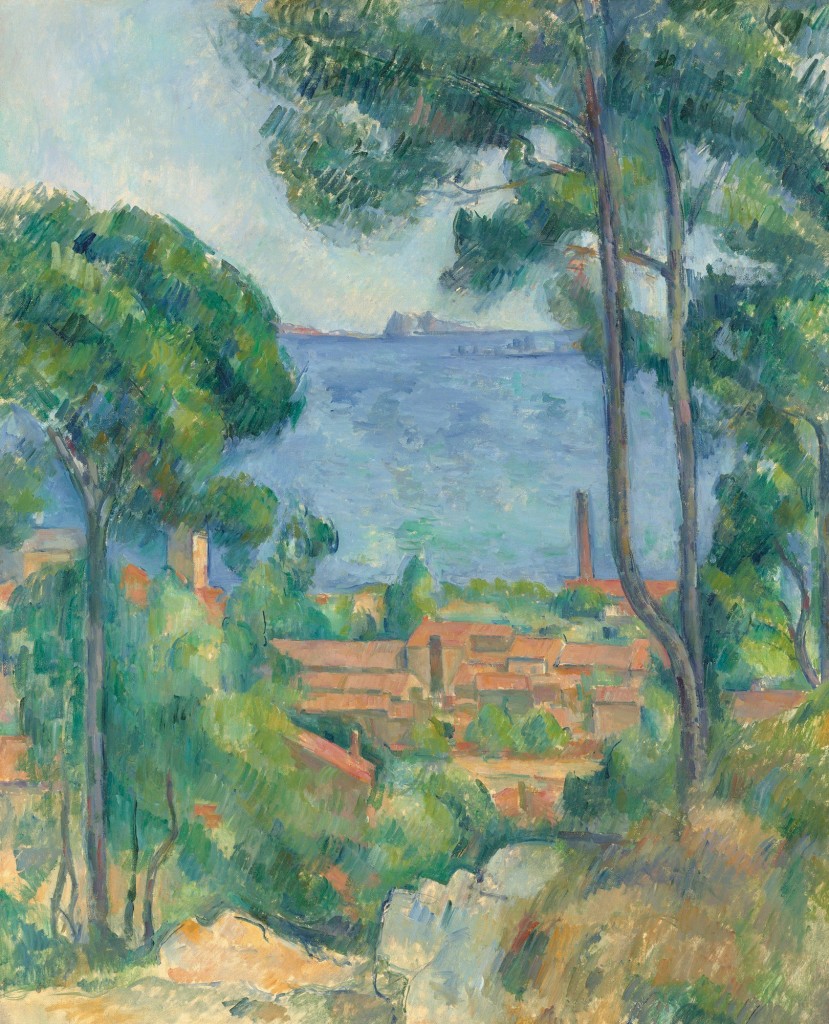

On February 4, Christie’s Impressionist and Modern Art sale in London will include Paul Cézanne’s Vue sur l’Estaque et le Château d’If. The painting was last sold in 1936 and is the first Cézanne landscape to come to auction in over a decade. It is from the collection of Samuel Courtauld and has been on loan to the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge since 1985. The low estimate, which is sure to be exceeded, is $12 million.

A recent report by the International Business Times identified that demand from Chinese collectors has inflated the market for works by Pablo Picasso by up to 300 percent. Christie’s and Sotheby’s will each have four works by Picasso in their February sales, including a significant maquette, Tête, that Sotheby’s estimates above $7.7 million.

The artist’s granddaughter, Marina Picasso, recently announced that she will sell seven works from her personal collection valued at $290 million. What a coincidence.